One of the most controversial topics in New York City is who counts as a “real” New Yorker. I’ve lived in Manhattan for the past 11 years but was labeled a “transplant” when I posted a video of a recent drive to my apartment in the city. My goal was to highlight any effects the new NYC Congestion Pricing Program could be having.

Let’s just say the video stirred up a bit of controversy amongst the 1.5 million and counting views (on Instagram alone). Some were incensed that they were being charged more to drive on roads they already pay taxes on. Others were enraged that I gave a positive perspective on the program and that “roads are now only for the wealthy.”

New York City is not the first place to try some form of congestion pricing or taxation program to disincentivize car usage. Before I give my perspective on our new program as a New Yorker (the first of its kind in the United States), let’s explore how it’s worked elsewhere around the world. And if you know who has final authority on who counts as a New Yorker, send them my way.

Congestion Pricing Programs Around the World

Singapore pioneered congestion pricing in 1975. It first started with a manual system that required licenses on windshields during peak hours. The system was electronified in 1998, allowing for more automation and sophisticated pricing.

Singapore’s current Electronic Road Pricing (“ERP”) system provides real-time variable pricing based on time of day, location, and vehicle type, among other factors. It has led to a ~24% traffic reduction, with revenue reinvested in Singapore’s transportation infrastructure (some of the best in the world).

Initial public resistance transformed into acceptance over time. Reliable travel times increased business productivity. Fewer cars led to emission reductions, with a 176,400-pound reduction in carbon dioxide. Singapore became a more pedestrian-friendly city with enhanced urban livability.

Their congestion pricing system, however, has not been without ongoing challenges. Equity concerns remain for lower-income drivers and the system’s complexity demands ongoing technical maintenance and administrative efficiency.

But overall, Singapore’s congestion pricing system has been a resounding success that’s supported by a large majority of the population. It’s been a model for other cities that have implemented similar programs, particularly London.

In 2003, London followed Singapore’s lead by implementing a congestion charging system (“Congestion Charge”). It charged £5 per day to enter Central London, raising the fee over time to its current £15 per day.

Like Singapore, the London system is electronic and automated. They have implemented numerous exemptions and discounts, including for residents, electric vehicles, and NHS patients, among others.

London initially enjoyed a ~18% reduction in traffic, but with the introduction of Uber and other ride-sharing services, congestion returned. The increase in bus and bike lanes in recent years has also contributed to more congestion.

The effectiveness of London’s system depends on who you ask. One thing is certain, however—over its 20+ years of operation, the system has generated some $3 billion that London has reinvested into public transportation. For anyone who has experienced both London’s Underground (the Tube) and New York City’s subway, the two systems are not comparable. London’s is far cleaner, safer, and dependable.

In addition to helping finance public transportation improvements, the UK government also highlights the following Congestion Charge accomplishments:

Limited traffic entering the zone by 18 percent during weekday charging hours;

Reduced congestion by 30 percent;

Boosted bus travel in central London by 33 percent; and

Enabled 10 percent of journeys to switch to walking, cycling, and public transport

Other cities around the world have had various successes and challenges with congestion pricing, including Stockholm and Milan. The lesson here is that congestion pricing is not a silver bullet solution. Critics have good reasons for opposing the system in New York City, particularly given equity concerns and NYC’s already high existing taxes.

A Summary of New York City’s Congestion Pricing Program

On January 5, 2025, New York City implemented a Congestion Pricing Program for vehicles that enter the Manhattan Central Business District:

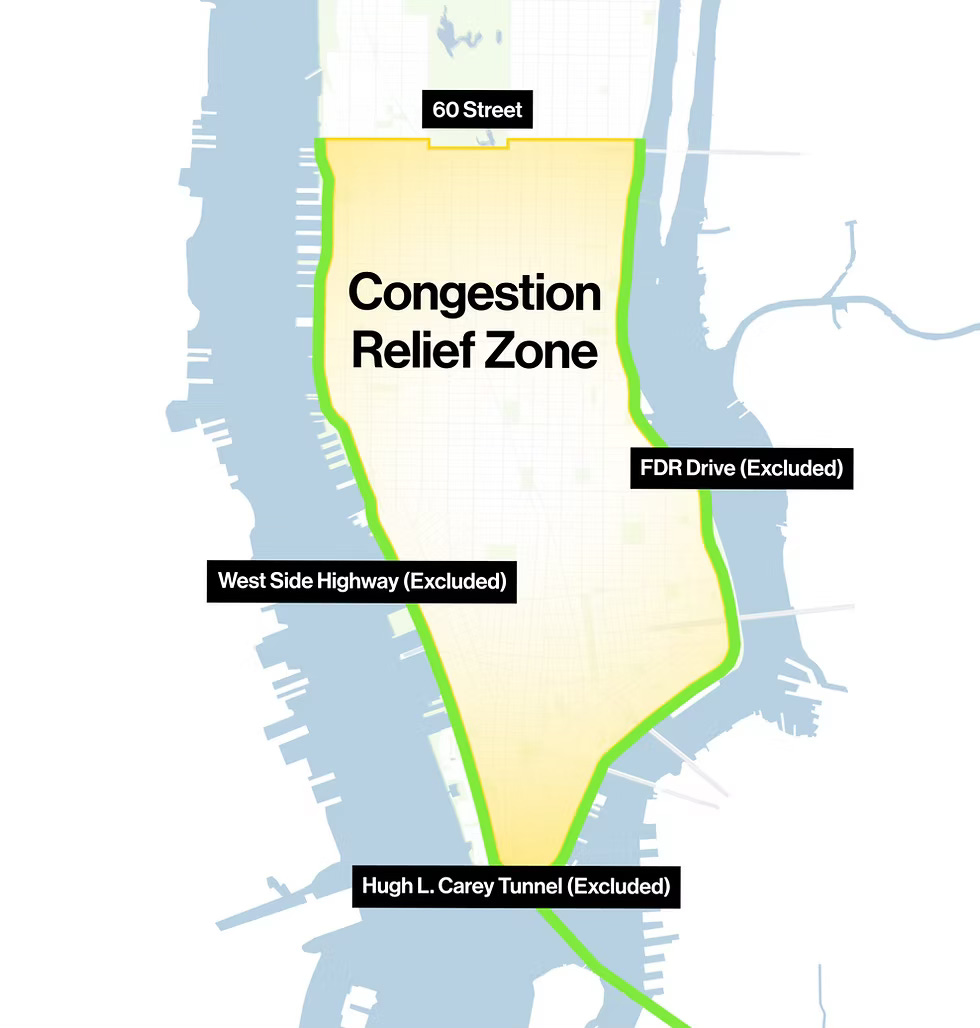

Drivers will be charged a toll on their E-ZPass once per day when they enter the Congestion Relief Zone. This includes streets in Manhattan below, and including 60 Street.

Similar to the Singapore and London programs, the goals are to reduce traffic and travel time, create safer streets and cleaner air, and improve quality of life. In addition, there are various discounts and exemptions, including a 50% discount for low-income vehicle owners.

The program is not without uncertainty though. Some roads are exempt, including the highways that run down the sides of Manhattan (the West Side Highway and the FDR), but it’s unclear what happens once you exit them within the zone. For example, if you notice from my video, I exited at Houston Street (well below 60th Street), but there wasn’t any tolling equipment that I noticed.

I was not immediately charged either. Three days later, the $9 charge was posted to my E-ZPass account, the electronic tolling program we use throughout much of America. But it’s still unclear to me how, where, or when I was charged given I entered Manhattan on an “exempt” road (the FDR).

Currently, the Congestion Pricing Program website states: “Tolling equipment will be on Broadway between 60 and 61 Streets.”

Does that mean they’re building tolling equipment at every exit off exempt highways or using existing cameras?

It’s also unclear what happens for New Yorkers like me who live within the zone but drive on the FDR and West Side Highway regularly to access neighborhoods like the East Village (also within the zone).

I’m sure this will all be sorted in time, but clear communication about these types of programs is crucial in the early days. Nobody wants to pay more unless it’s clear when and how they will be charged and with an understanding of how the benefits outweigh the costs.

For many New Yorkers, those benefits are still very unclear.

The Case Against NYC’s Congestion Pricing Program

The primary argument I’ve heard against the program is that we’re being charged to drive on roads we already pay taxes to maintain. Why doesn’t the city or state already have the money to maintain the subway, roads, and other forms of public transportation? New York City is one of the highest-taxed cities in America, after all.

The problem with this argument is that existing taxes don’t deter drivers. The taxes used to maintain existing NYC infrastructure don’t incentivize alternative means of transportation. And NYC has the world’s worst traffic congestion.

NYC’s Congestion Pricing Program, by contrast, will at least make people stop to consider how they want to enter the city now that most vehicles will be charged $9 (plus other tolls).

But doesn’t this just divert the traffic elsewhere?

Those making this argument miss the goal of most drivers — getting into the heart of Manhattan. If that’s the mission, traffic won’t be diverted elsewhere because there’s only one Manhattan for work and play. Although it may incentivize them to carpool, take the train, use a water taxi, or ride some other form of mass transit.

Then there are the inherent inequities. Rich vs poor. Haves vs have-nots. I think this is the most compelling argument against the program. It’s something London and Singapore still struggle to address.

NYC has at least made an effort to address it by giving low-income vehicles a 50% discount. And let’s be honest, it’s not like someone working at a neighborhood deli was driving into Manhattan every day and paying for $50/day garage parking or buying a monthly pass that can reach $1,000/month.

But even if it doesn’t have a major practical effect, the perception that the roads are only for the rich in New York City is not a good look. The plumber, electrician, or blue-collar worker trying to enter the city in their utility van should not be forced to pay the full amount. Service workers who work odd hours and may not be comfortable taking the subway in the middle of the night should not be unduly punished either.

The city and state must prioritize fixing the subway and making it safer as soon as possible if the Congestion Pricing Program is going to succeed. That means more trains that can handle a larger number of riders and more police and social workers to monitor and assist on trains and platforms.

Despite all of these challenges and fair criticisms, I’m in favor of NYC’s program.

Why I Like NYC’s Congestion Pricing Program

One of my favorite parts of visiting European cities is the pedestrian-only boulevards. Like London’s Carnaby Street. La Rambla in Barcelona. Ponte Vecchio in Florence. Vitosha in Sofia. Aleksandrovska in Burgas.

Manhattan has none of these streets. Unless you count walking paths along the West Side Highway or the summer streets that occasionally close parts of Park Avenue. Maybe South Street Seaport or Stone Street count?

There’s no reason why a street like Broadway should not be pedestrian-only. Why parts of 5th Avenue should not be pedestrian-only. Madison Avenue!

Can you imagine how enjoyable that would be? Then we could perhaps have real al fresco dining in Manhattan, not the cardboard box variety that has thankfully disappeared more the further we’ve drifted from the pandemic years.

A Manhattan that prioritizes pedestrians and quality of life while deterring cars is a metropolis of the future that will thrive. As technology improves, there’s no reason we need cars in every nook and cranny of the city. We must move on from a car-centric world in American cities, not only for environmental reasons but for community as well.

We have lost our sense of community. From social media to working from home, so many forces have caused many of us to isolate further and remove the happenstance encounters with other humans that used to be regular occurrences. As a millennial, I’m grateful to remember such a world before smartphones and social media.

A Congestion Pricing Program that deters cars and helps fund the public transportation of the future is something we should all support. Provided of course that it accounts for inequities and clearly communicates how, what, and when everyone will be charged.

New York must do a better job at marketing. The benefits must be clear. Otherwise, people are just going to remember the $9 cost every time they hit 60th Street in Manhattan.

This is a great opportunity for New York City to innovate and modernize its transportation. Perhaps even resurrect some of the good of Robert Moses, while leaving all of the bad, to prove to the world once again that it’s still the greatest city.

New Yorkers should seize this opportunity. Whoever qualifies.

For more from John, follow him on YouTube, Instagram, Threads, and Medium.